Mary Plantation History

Mary Plantation

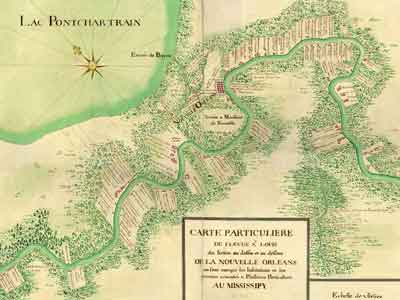

It is not known exactly when Mary Plantation was built, though the land seven leagues below New Orleans on the left bank of the Mississippi river, was originally settled by the Chaouchas Indians. Early European habitation was recorded on a 1723 french colonial map of Louisiana. According to the American State Papers, a prominent Frenchman, Louis Martin Bragner De Clouet, a critical figure in the development of New Orleans and the land below it, acquired this tract of land in 1774 from a complete Spanish Land Grant. Based on Historic Analysis, the original two-room house may have been built at this time. The Norman Truss which supported the original double pitch pavilion roof is still present in the attic. In the late 18th century Joseph Dalcour, a prominent French Colonial planter, assembled several thousand acres of land, which became the Plantations of Stella, Mary and Terre Promise’ (Promised Land).

On October 12, 1827, an uninterrupted chain of Title begins with a property transfer of the land know as Mary between John Morris and Manuel Andry. At this time there was an inventory of property, including a barn, slave quarters, out buildings, a sugar mill, a United States Government Building, and a main house that was Mary, unfortunately, all archival records were destroyed by fire in the Notary’s Office.

On February 26, 1826, under the notarization of Felix de Armas, Manuel Andry exchanged property to Francois Chauvin de Lery (Delery), and his wife, Marie Coutton Desilets. It is speculated that, under the ownership of the Delery family the first expansion of Mary begins. The original one room deep, West Indian style Creole house was remodeled to a straight line, pavilion roofed structure, two deep with surrounding 10 foot galleries on all four sides. The first floor of the house was of solid masonry construction with square brick columns. The second level was of cypress heavy-timber construction with brick infill. Slender chamfered cypress columns supported the roof at this level. All millwork was of cypress, and the original roof was probably of cypress shingles. An unusual of this expanded and matching door split at the front façade. According to the descendents of a later owner, Simeon Mathe, there were two exterior stairways in the Creole tradition.

By an act of succession passed before the notary Charles Dutillet on June 13, 1845, Jules, son of Francois and a well known sugar planter, acquires the property. At this time an inventory of the succession defines the land, built improvements and names, ages, and skills of all slaves. On September 7, 1866, Jules delery sold the property to Simeon R. Mathe. After the passing of Simeon, his wife, Mrs. Dorestine Reggio, acquired the property, and on March 4, 1911, she sold the property to Fidelity Land Company.

Fidelity Land Company developed a systemic pan of house sites, farm blocks, streets and parks, which became known as the town of Dalcour. Several of these sites were sold or leased, including the home site known as Old Dalcour (Mary), having the boundaries of the property as it exists today. The land site was sold to Capital Interstate Trust and Banking Company on September 9, 1918. The town of Dalcour never becomes a viable economic entity due to the location of the new United States Nave Base on the West Bank of the Mississippi at Belle Chase.

A Chicago investor, E.A. Schneider, purchased the property from Interstate Trust on January 24, 1919, and after three years, he sold the property to Rural and Urban Realty Company. A series of subsequent land exchanges took place an Mary was often abandoned and neglected. On March 24, 1945, Herbert Moffet purchased the seven acre site with the intent of demolishing the old structure and utilizing the land for a new home. Demolition cost proved to be too high, causing him to sell the house to the Knoblocks.

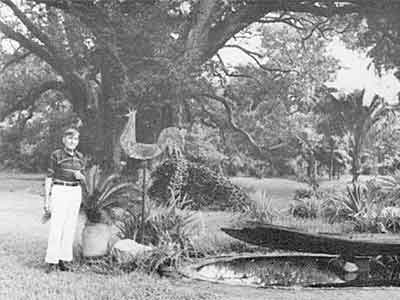

The seven acre plantation was purchased in 1947 for $6,000.00 by Elmer ‘Eric Knoblock and his wife Marguerite. The plantation was originally purchased as a bird watching haven, with its exotic landscape and ancient mighty oaks. Eric, a nationally recognized botanist, intended to transform the landscape into an array of palm and citrus trees, along with flowers and exotic Bromeliads. The were known for their involvement with several significant preservation groups, including founding ‘Patio Planters’ in the Vieux Carre and the ‘Palm Society’, Eric, himself was one of the founders of the ‘Bromeliads Society’.

Shortly after the Knoblocks purchased Mary, the decided to restore the badly decaying house, due to a growing respect for preservation. It was their intent to develop Mary into a home in which they could live, not a public landmark. They contracted a well-known local master craftsman, Carl Hithe, who displayed an incredible intuition for reconstructing old places. He began with using old materials from abandoned homes and demolition yards to maintain a certain character and style. The practice of adding and reusing materials was reflective a true Creole nature. Approximately 75% of what is visible today is part of the original construction. The galvanized roof, which originally of cypress shingles was replaced with second-hand slate to give it a weathered look. The roof timbers were structurally reinforced and the surrounding galleries were restored. However, the most significant change was the replacement of the heavy brick columns on the ground floor. Narrower molded concrete columns stand in their place, reflecting the popular taste and opinions of that time as to what constitutes Creole architecture.

The idea of reusing old materials was carried through on the inside as well; antique cypress dominates the interior along with brick and slate. On the ground level the deteriorating brick floor has been covered with bricks from the Old Southern pacific Passenger Station in New Orleans, set here in a basket weave pattern, while the ceiling has been covered with twelve inch tongue and groove cypress boards. Two adjacent rooms were transferred into one, connected by and archway, creating a combination kitchen/dining room. Over the dining room table, hanging from the original iron works is a reproduction punkah used in the 18th and 19th century as a shoo-fly. A lavatory, constructed of cypress panels, was added in the first floor hallway as a modern convenience. The first floor parlor mantle has been restored, however the mantle in the dining room is missing.

The upstairs floor has been replaced with a series of twelve inch planks of antique cypress in a herring bone pattern and is held in place with wooden pegs. Once again, this style of reusing old materials is reflective of that time. Two bathrooms were added with second-hand slate flooring, along with three closets. These were all constructed of cypress panels and millwork to reflect a natural finish. Antique mantles, with missing columns, have been partially restored and a cypress staircase has been added to the attic. The interior renovations further emphasized the Knoblocks’ intent, to utilize Mary as a home in which they could live.

It was during Hurricane Betsy, 1969, that the Knoblocks first met John Redfield, a commander at Belle Chase Naval Base. Their friendship with John and his Concern for the preservation of Mary flourished. Having no children of their own, the Knoblocks willed Mary to John Redfield. In January of 1979, Eric passed away and Marguerite, with the help of John, continued to live and care for Mary. Marguerite was struck with an incapacitating illness in 1985, and at this time, John’s son, Tom, moved into the plantation and the two of them continued to care for the house and its beautiful landscape. Marguerite Knoblock passed away in November 1994, and today, Tom Redfield, his wife, Elissa, and their son Rawlin are keeping the Knoblocks’ dream alive by preserving Mary Plantation as their home.

During the spring semester, 1995, a Historic American Building Survey (HABS) Grant was awarded to Mary Plantation, from the Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism, Division of Historic Preservation. The project was completed under the direction of Tulane professor, Eugene D. Cizek, Ph.D., A.I.A, and a group of student architects: Sara Amorsino, Vanessa Cayette, Charles de Jesus, Vasso Elefther, Amy Gerber, Robin Komar, Charles R. Maroney, Marie Palumbo, Brian Pignanelli, Rebecca Salman, Evan Siegel, and Patrick Wood. Tulane Professor of Botany, Steven Darwin, Ph.D., and historian William de Marigny Hyland served as consultants.

In the Spring of 2012, Mary was purchased by Blake Miller, a New Orleans Hotelier. Mary was just readying to open to the public when hurrican Isaac swept through Louisiana and put the hurt on Braithwaite, Louisiana. Mary and most of the city of Braithwaite was devastated and put under fourteen feet of water.

Although many folks abandoned their homes and property in Braithwaite for fear of future hurricanes, Blake Miller was determined to restore Mary to her original beauty. Mary and her grounds are now fully restored with recent additions that include a meandering walking path that connects the grounds of Mary. In early 2015, a wonderful Reception Barn will open that will accommodate up to 320 guests. Ideal for wedding receptions and events of all kinds.

Mary Plantation Introduction

circa 1790s and circa 1827

Narrative by Ann Mason

While much of Mary Plantation’s history is undocumented, the charm and architectural importance of this early Creole planter’s home is uncontested. One of only four residential buildings in Plaquemines Parish listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Mary was also recorded for the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS). Along with some three dozen structures around Louisiana, it is a rare survivor of the building traditions characteristic of French America. Generally termed “French Creole” architecture after the French Colonial period (1699-1762) during which the type developed, the plans, construction methods, and ornamental traditions were so well-adapted to the environment and the needs of the settlers that they continued to be popular throughout the Spanish era (1763-1803) and well into the American period.

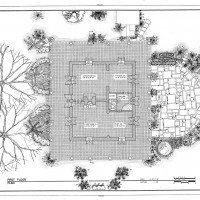

Recent owners added modem conveniences, but did not eliminate the qualities valued by Louisiana’s settlers-the sturdy soft brick and cypress construction, broad galleries under a sheltering roof, and generous French doors to let the breezes through. Once surrounded by fields and outbuildings, the home now stands on approximately 7 1/2 acres of high ground near the Mississippi River before a grove of ancient oaks. During the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the house was the center of an agricultural village and home to generations of planters’ families, but in the twentieth century, Mary Plantation suffered from neglect until purchased in 1946 by Eric and Marguerite Knobloch. The couple renovated the building, surrounded it with a splendid collection of rare bromeliads, and opened the home for tours and renowned picnics. Given new life by the Knoblochs, the house has since been ardently maintained and further updated by historic preservationist and noted antiquarian Blaine Murrell McBurney and his wife, Stephanie Finch McBurney, the current owners. The house has served as a family home and a country retreat.

Setting & Background

Mary Plantation is located about 22 miles downriver of New Orleans on the East Bank of the Mississippi River in Plaquemines Parish. The unique name of the parish is taken from the Indian word “piakimin” for persimmon, which French colonial governor Bienville found growing abundantly in the area around a rough fort the settlers established about 1700. Just upriver of the old house is English Turn (Detour des Anglais), a landmark sharp bend in the Mississippi River that has proved difficult to navigate for three centuries. Legend has it that the bend acquired its name during a chance encounter between Bienville, who was headed downriver in a small boat, and the captain of an English sloop headed upriver in 1699. The Frenchman lied boldly, saying that the French had established a strong fort slightly upriver, and the English explorer believed his statement, turned his ship around, and left the entire territory to the French.

During the early eighteenth century, French military engineers designed a beacon for guiding ships to the mouth of the river and a barracks for soldiers at La Balise and established forts to protect the lower Mississippi from incursions by the English and Spanish. The area was soon settled with concessions for growing indigo, rice, tobacco, and oranges. The parish was created in 1807, and the large settlement of Pointe a la Hache was selected as the parish seat in 1846.

By the early 1720s, the three Carriere brothers had obtained concessions or land grants just below English Turn in the area of Mary Plantation. Shown on a period map just downriver is the village of the Chaouachas, a relocated group of Amerindians, whose name was applied to a large concession on the West Bank of the Mississippi. Inventoried for a 1737 sale, this prosperous concession featured a one-story main house framed with wood filled between the members with bousillage (a mixture of mud, Spanish moss, and animal hair), a bark-roofed kitchen, an old pigeon house, a dairy, a chicken house, several barns, stables, and storerooms, three tobacco sheds, four indigo works, and twenty negro cabins roofed with palmetto. The quantity of farm implements, slaves, and general improvements attests to the huge amount of money and labor devoted to developing successful farming operations in the wild landscape. From New Orleans downriver to within about thirty miles of the mouth of the Mississippi, concessions were granted with the provision that the ground be cleared and the land put into use. The Carriere concessions in the neighborhood of Mary Plantation were probably quite similar to Chaouachas, although perhaps smaller. The map shows an assortment of small buildings framing a main house.

The most important cash crop for eighteenth century planters was indigo, the production of which was encouraged by the French government. The plant was well-suited to the climate and relatively cheap to tend. Most plantations had one or more indigo works where the harvested plants were soaked and fermented in water, the liquid strained and agitated, and the result mixed with lime before being dried. While noxious, the process was comparatively inexpensive and used little equipment. Indigo production ceased to be profitable on a commercial scale by about 1800, but planters continued to grow small quantities in south Louisiana. An 1864 report from Plaquemines Parish comments that the indigo grown there was “much esteemed for its beautiful color and good quality.” Descendants of the old crop can still be found growing wild in hedgerows and fields.

An 1809 newspaper reported the general conditions just as agriculture was moving from indigo to sugar:

“There are no lands worth settling at present between the Balize and Fort Plaquemines. In the neighborhood of the fort, are several rice plantations. The land from the Fort to New Orleans grows better, progressively, but none of it is worth settling more than from half to three quarters of a mile back of the river on either side. There are valuable rice and sugar plantations on the river, between New-Orleans and Plaquemines. Oranges grow in abundance on almost every plantation. Alligators at this season of the year, are to be seen in the river in great supply.”

By the early nineteenth century, sugar was rapidly replacing indigo as the area’s chief crop. Spurred on by new varieties of cane and Etienne de Bore’s successful experiments resulting in the granulation of sugar from cane juice, the industry took hold along the Lower Coast. Despite the need to invest heavily in mill buildings, machinery, and slaves, planters quickly shifted to the new crop. By 1852, Plaquemines Parish was reported to have 205 plantations with nearly 12,000 acres in sugar cultivation, 913 acres in rice, and 3,900 acres in com. Production resulted in 12,686 hogsheads of sugar and nearly half a million barrels of molasses. There were then 615 families comprising a total free population of 2,611 persons and 4,779 slaves.

In Plaquemines Parish, rice continued to be an important product, along with com and hay for livestock and vegetables for home use and for sale in New Orleans. Cattle, sheep, hogs, and fowl were raised, and an extensive fishing and oyster industry developed during the nineteenth century. First from clearing the agricultural land and later from cutting in the back areas, lumbering was also an important source of income for many planters. The area was reportedly covered with the cypress trees highly sought after for building. Oranges were a prominent crop from the eighteenth century on and can still be seen in the upper sections of the parish.

Reports suggest that planters in the area were plagued by storms, floods, droughts, caterpillars, and diseases that destroyed their crops, by cholera and yellow fever outbreaks, and by economic difficulties, but still they persisted in their occupation of this rich, but capricious environment. They must have believed, as did a nineteenth century writer: “This section may, without the least exaggeration, be called ‘the best land in the world.’ The rivers and bayous furnish fish and oysters of finest flavor; the earth brings forth fruit and vegetables in tropical abundance; all the conditions of life are easy; and, in addition, there is the profitable culture of sugar and rice.”

Mary Plantation House

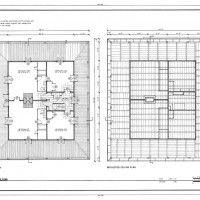

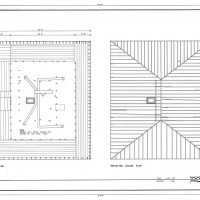

Mary Plantation is a classic example of the French Creole planter’s home. Without hallways, the house contains two large front rooms and two smaller rooms flanking a small entry room with a stairwell in the rear. The ground floor walls, originally coated with soft stucco on the exterior, are about sixteen inches thick and made of somewhat irregular soft reddish brick. All openings on this level are spanned by jack arches, but several on the front have been altered during modern renovations. The original brick columns were replaced by the Knoblochs during the mid-twentieth century with cast concrete columns of approximately the same size.

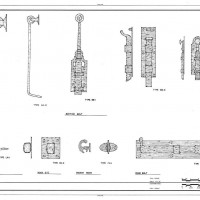

The second floor is brick-between-posts construction plastered on the interior. The 10-foot deep gallery is supported by chamfered cypress posts, the ones on the front being nicely detailed. The cypress French doors, most with their original wrought iron hardware, are tall and thin, with 12 small lights (window panes) above a single panel. The double-hung windows on the sides are pegged together and small-paned. Most of the shutters are original and made of wide cypress boards with iron strap hinges, some of which are hung on plate-mounted pintels typical of about 1830, while others are installed with the earlier drive pintels. Several with more narrow boards may be replacements. On both levels, the joists supporting the floor boards above are exposed, as in most buildings of the age, but, unlike more sophisticated examples, the joists are not beaded.

The plan is typical of the Creole planter’s homes built in Louisiana during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Having discovered that New Orleans and its environs were subject to flooding, settlers adopted the concept of raising the principal living rooms on a tall brick basement. Thomas Hutchins published his description of Louisiana in 1784. Local homes, he said, “generally [are] built with timber frames raised about eight feet from the ground, with large galleries round them.” Cellars could not be built because “any subterraneous buildings would be constantly full of water.” In addition to preventing water damage in the main portions of a home, the raised basement also exposed the main rooms and galleries to more of the prevailing winds. With windows or French doors on the building’s four sides, air circulation remains excellent. Ground floor rooms were used primarily as plantation offices, storage rooms, pantries, and dining rooms convenient to the separate, outdoor kitchens. Above were the principal living and sleeping chambers.

Mary’s floor plan represents an interesting variation on the typical arrangement of en suite rooms with stairs located outside under the gallery. Here, as at the Petit Pierre House (Baton Rouge, c. 1815) and Chretien Point (Opelousas, 1830), the stair is within the main walls, located at the rear of the house in a small entrance room flanked by larger rooms in the position of cabinet. This arrangement was perhaps dictated by the home’s original configuration with only limited gallery space. From the shape of the chamfered posts and the roofing system, it is clear that the gallery was enlarged early in the history of the house. At first only across the front(and possibly the rear), deep galleries were added, probably about 1830, to the other sides to enlarge the living space. The only other significant change to the plan occurred during the Knobloch ownership when arches were cut between the ground-floor rooms. The present gallery stairway was added quite recently and serves as a convenient alternative to the small, steep stairway in the rear.

Broad galleries served several purposes. First, they shaded the walls and made homes cooler. Doors leading onto the galleries could be kept open, even during the heaviest rainstorms, because of the protection provided by the wide outdoor spaces. The most important aspect of this design was to provide relatively cool outdoor living spaces that could be used much of the year. Ladies sat there to read or sew in natural light, children played, and men frequently slept in hammocks hung on the gallery posts on warm nights. Major Amos Stoddard wrote in 1812: “The arcades or piazzas afford agreeable shades, under which the inhabitants repose themselves during the heat of the day; they likewise serve to shelter them from the dews and rains; and many families eat and sleep under them in summer.”

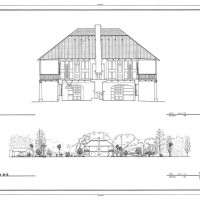

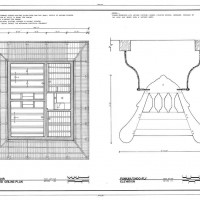

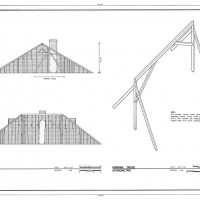

The roof is constructed in a French Colonial manner with heavy cypress timbers pegged together in a technique stretching back to Medieval times. The usual method in Colonial Louisiana was to saw the timbers and carefully fit them together on the ground. Roman numerals and positioning marks facilitated the erection of the colombage frame on the brick base, and these can be seen on the attic timbers. As shown on the HABS cross section of the house, contained within the main framing is an early cypress truss that would have served to support the roof of a building about fourteen feet deep. It has been postulated that this is the remnant of an earlier home that was enlarged and renovated at a later date. If true, that building may have dated from about 1795 when François Delery first obtained the property. Indeed, some features of the building seem to date from the 1790s. However, the main visible portions of the existing house are more typical of the late 1820s or early 1830s, which fits well with the documentary evidence of Francois Chauvin Delery’s 1828 acquisition of the property, shortly after which he might have significantly enlarged and rebuilt the home.

Although the framing is original, the roof’s slate surface in not. When built, the building probably had a cypress shake roof of the type common in both the city and country. This was later changed to a galvanized metal roof that was replaced with slate by the Knoblochs. A more durable material creating a less leak-prone roof surface, slate was increasingly popular throughout the nineteenth century, and nearly all old roofs on substantial buildings were replaced with it.

The front facade on the upper floor is quite elegant and clearly the most important portion of the exterior. With its beaded corner members, chair rail, and stucco over brick-between-posts construction, it resembles an interior space. The other three sides retain the original deep, beaded cypress weatherboards in which are many wrought-iron nail heads.

Building Type and Style

Scholars debate the origins of the distinctive French Creole planter’s house type but it is clear that the influences are basically European-the first such structures were designed by well-trained French military engineers. Settlers incorporated features developed in sister French colonies, such as Quebec, Martinique, Guadeloupe, and what is now Haiti, all of which were well-developed at the time Louisiana was founded. Some colonists emigrated from these areas, bringing their architectural ideas with them, perhaps including the useful wide galleries that provided outdoor living space in the sweltering Caribbean. These homes were well-adapted to the climate, available materials, and life ways found along the Gulf Coast. Taken together, these influences resulted in a distinctive and now-rare building type.

Originally, the word “Creole” referred to the children born in a colony of European parents, and, indeed, homes such as Mary Plantation were born at the edge of the wilderness of long-standing Old World traditions.

Whether built during the French, Spanish, or American periods, typical French Creole homes shared a number of distinct characteristics, including:

• Colombage frames made of local cypress members pegged together using typical French joinery techniques;

• Walls made of solid masonry on the lower floor rez-de-chausse’e) with the spaces of the upper floor colombage frame filled in with either brick brique-entre-poteaux or bousillage, a mixture of mud, Spanish moss, and animal hair;

• Wide galleries on one or more facades supported by slender chamfered posts (as at Mary Plantation) or simple turned columns;

• Large, sheltering hipped roofs that are frequently double-pitched;

• A main living floor (premier e’tage) raised from four to ten feet above the ground,

• French doors with small window panes and simple wrought-iron hardware;

• Floor plans without hallways, but generally with small rooms called “cabinet” located at the rear of the house;

• Stairways located under cover of the gallery or in an inconspicuous comer;

• Room placement without regard to symmetry, but with attention to convenience, air flow, and ease of living.

By the 1830s, Anglo-American traditions began to influence architects and builders, although the old traditions persisted in many areas. Homes with center halls became popular, bousillage was relegated to the countryside, and Louisiana residents joined the rest of America in emulating the buildings of ancient Greece and Rome.

Twentieth Century

The property remained in the hands of Simeon Mathe and then his wife, Dorestine Reggio Mathe, until sold in 1911 to the Fidelity Land Company, which soon announced a novel approach to redevelopment of the large tract containing the home:

“On the property is an old plantation house, built along the architectural lines of antebellum days. To preserve this building, because of its association with the history of this section of Louisiana, the company intends to renovate the dwelling and use part of it for a permanent exhibit of the products, not only of the property itself, but of the surrounding country. There is room in the house for a modern restaurant which would be an innovation, not only for the pleasure-seekers who drive their automobiles over the roadway, but others who will visit the territory for business or investment.”

In front of Mary, the Louisiana Southern Railway intended to erect a “modern pagoda station,” and the improved access prompted the developers to say: “This part of Plaquemines Parish will become the Mecca of home-seekers.” Apparently nothing came of the scheme, but anticipation of the new railway station seems to have been important to the company’s plan to subdivide the tract to create the settlement of Dalcour immediately upriver of the home. While less successful than the developers hoped, the area grew up as a small residential community. The land now comprising Mary Plantation was carved out of the larger tract at this time.

In 1918, the some six-acre plot was purchased by Capital Interstate Trust & Banking, which held it for only four months before selling to Chicago investor E. A. Schneider. The owner in 1923, the Rural Urban Realty, Inc., represented by attorney John Perez, claimed to have “from $15,000 to $20,000 invested in the property known as the Dalcour or Mary Plantation.” The company was then involved in a dispute with the Dalcour Hunting Club concerning access to the land. Subsequent commercial transactions suggest that the building was little occupied and gradually

fell into disrepair.

In 1946, Eric and Marguerite Knobloch purchased some six acres with the old plantation house for $6,000. A nationally known botanist and expert on bromeliads, Knobloch and his wife devoted thirty years to the transformation and enjoyment of Mary Plantation. In 1972, Eric Knobloch authored an article in the journal of The Bromeliad Society, Inc., of which he was then Second Vice-President. Entitled “The Bromeliads of Mary Plantation,” the piece chronicles the growth of Knobloch’s hobby into a near obsession that resulted in the purchase of Mary Plantation. He recounts, “Such an avid accumulator was I that our small patio garden and greenhouse in New Orleans was soon bursting at its seams. With the idea of expanding, we acquired in 1946 six acres of jungle below New Orleans containing magnificent live oak trees (Quercus virginianai).

Shrouded in this tangle of trees and vines, moreover, stood the ruins of the 200-year-old Mary Plantation House … Although we did not render the house habitable until 1954, from the very beginning, epiphytic bromeliads were established at random in the trees and shrubs and on and among the bark-covered roots of the giant oaks.” Although his extensive collection of more than 300 varieties of bromeliads have largely disappeared, huge clumps of the plants remain nestled at the base of the oak trees and others are scattered in the grounds. The Knoblochs also planted 100 palm trees, 37 persimmons, pecan and black walnut trees, and several varieties of citrus.

During the late 1950s, shortly after completing the major renovations, the Knoblochs began to host tours and picnics for preservation and naturalist groups, such as the Louisiana Landmarks Society, Patio Planters, the Louisiana Bromeliad Society, and Spring Fiesta. For the next decade, the home was host to hundreds who happily boarded buses for a country afternoon in Dalcour. Eric died in 1979 and Marguerite in 1994, leaving the property to friend and fellow lover of Mary Plantation, Commander John Redfield, USCG (1917-2004).

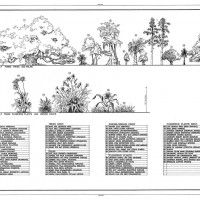

HABS Survey

During the spring semester, 1995, a Historic American Building Survey (HABS) Grant was awarded to Mary Plantation, from the Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism, Division of Historic Preservation. The project was completed under the direction of Tulane professor, Eugene D. Cizek, Ph.D., A.I.A, and a group of student architects: Sara Amorsino, Vanessa Cayette, Charles de Jesus, Vasso Elefther, Amy Gerber, Robin Komar, Charles R. Maroney, Marie Palumbo, Brian Pignanelli, Rebecca Salman, Evan Siegel, and Patrick Wood. Tulane Professor of Botany, Steven Darwin, Ph.D., and historian William de Marigny Hyland served as consultants.

The beautiful line drawings of Mary Plantation featured on her website were a part of Mary's HABS survey.

Present Day @ Mary

Construction is under way at Mary Plantation. Opening in early 2015 will be the Mary Plantation Reception Barn that can host up to 320 guests, In addition, Mary is adding a new Guest House on her newly expanded plantation grounds